– How do I do this?

– What Barriers Might I Run Into and What Are Solutions?

– Where do I go for more resources?

– References

Challenging behavior can interfere with children’s learning and can even be harmful to the child and others. Working with children with challenging behaviors can be stressful for providers, teachers, and caregivers. Part of a multitiered system of support, Tier 3 includes practices for providing individualized, more intensive interventions to children with persistent challenging behaviors when other approaches have not been successful.

Tier 3 practices focus on performing a functional behavioral assessment (FBA) and developing a behavior support plan.

Functional behavioral assessment (FBA) is mandated by law and is a systematic process for collecting information about why a child’s challenging behavior occurs. FBA gives a clear description of the challenging behavior and its context, and helps explain why the child engages in that behavior.

The information gathered from an FBA is used to develop an individualized behavior support plan. Behavior support plans address what events or circumstances trigger the challenging behavior. Plans also include instruction on how to help the child learn more appropriate social and communication skills and strategies that caregivers can use for responding to the behavior so that it is not reinforced.

A team-based approach is key. It is important to remember that performing an FBA and developing a behavior support plan is most successful when using a team-based approach guided by a knowledgeable facilitator (e.g., behavior specialist, mental health consultant, social worker, trained staff member). Other potential team members may include the child’s parents, teachers, school administrators/directors, childcare providers, therapists, other caregivers, and other family members.

Functional Behavioral Assessments and Behavior Support Plans are complementary. Active participation and collaboration among team members is essential to understanding the purpose of a child’s challenging behavior and appropriately responding to it. The complementary process of conducting an FBA and using this information to develop a behavior support plan can promote children’s social and emotional skills and reduce challenging behaviors before they lead to suspensions or expulsions in early childhood settings.

How do I do this?

Step 1. Discuss and reflect. Discuss with your providers/teachers the importance of using a systematic process to understand how, why, and when a child’s challenging behavior occurs. This information can be used to develop an effective behavior support plan.

- It is important to recognize what systems and practices are currently in place to address challenging behavior. Providers/teachers and staff should be supported as they reflect on their own practices. It may be helpful to ask questions.

- It can also be helpful to discuss to what extent practices that are specifically relevant to FBA and behavior support plans may or may not be present. Providers/teachers may already be engaged in these steps but call it something else.

Step 2. Support providers/teachers in documenting the behavior.

- The nature of the behavior. Provide a clear description of the behavior. What, specifically, does the child say or do? The behavior should be observable, measurable, and precise.

- What happens just before the behavior? Write down the specific predictors and setting events leading up to a challenging behavior. This can help in understanding what triggers the behavior and under what conditions the behavior is likely to occur.

- What is the response to the challenging behavior? Observe the events that follow a challenging behavior. This can help providers/teachers and caregivers understand what is maintaining the challenging behavior.

- Why the child might be exhibiting the behavior? It is important to understand the purpose or function of the child’s behavior. How is it “working” for the child, and what does the child get out of it?

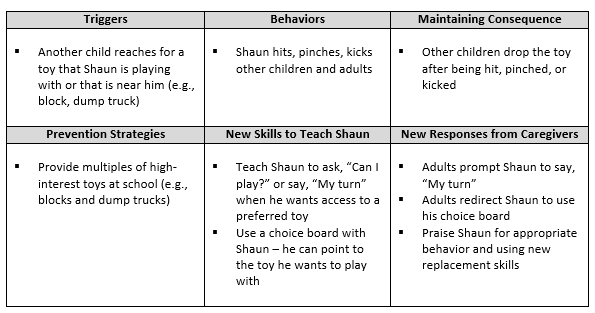

Vignette 1: Shaun’s disruptive behaviors include hitting, pinching, and kicking other children and adults.

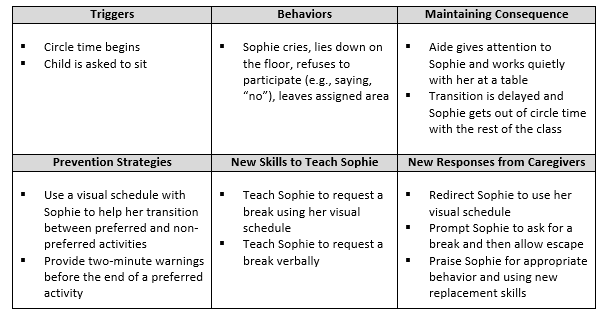

Vignette 2: Sophie’s disruptive behaviors include crying, lying on the floor, refusing to participate (e.g., saying, “no,”), and leaving the assigned area.

Vignette 1: Shaun is playing with the blocks and a dump truck, and another child reaches for a block. Shaun tends to exhibit challenging behavior in the block area or sandbox when another child tries to take a toy he’s playing with or a toy that is near him.

Vignette 2: Sophie’s provider announces that it’s time to transition to circle time activities. Sophie tends to exhibit challenging behaviors during non-preferred activities like circle time.

Vignette 1: When Shaun hits, kicks, or pinches other children, they drop the toy and pick a new one.

Vignette 2: When Sophie cries and leaves the carpet during circle time, her provider, Mr. Brown asks the aide to talk and work with Sophie quietly at a table.

The function of a child’s challenging behavior may not be obvious. In some cases, the function may change over time or serve multiple purposes. Continue to collect data to gather more information and discuss how to proceed with the behavior support team.

Step 3. Use the information to develop a hypothesis. Information that is gathered and documented during a functional behavioral assessment is used to develop a behavior hypothesis statement. This is a “best guess” about why the child’s behavior is occurring.

Vignette 1: When another child tries to take a toy that Shaun is playing with or near, Shaun hits, kicks, or pinches the child. As a result, the other child drops the toy and finds a new one. Shaun uses this behavior to obtain desired toys.

Vignette 2: When the provider announces it’s time to transition to circle time, Sophie cries and refuses to participate, either by lying on the ground or running away. As a result, the provider asks the aide to quietly work with Sophie at a table. Sophie uses this behavior to escape non-preferred activities and obtain attention from an adult.

Step 4. Use the information from the functional behavioral assessment and behavior hypothesis statement to develop a behavior support plan. The behavior hypothesis statement provides an assumption about the function of a child’s challenging behavior. It is central to developing an individualized, assessment-based behavior support plan to address a child’s persistent challenging behavior. A behavior support plan is designed to do the following:

- Provide prevention strategies. Prevention strategies are ways to make events and interactions that predict challenging behavior easier for the child to manage. When used, prevention strategies reduce the likelihood that a challenging behavior will occur. They may include environmental arrangements, personal support, changes in activities, new ways to prompt a child, or changes in expectations.

Vignette 1: Ms. Flowers helps the behavior support team brainstorm strategies to prevent Shaun’s hitting, pinching, and kicking. Since Shaun engages in these behaviors to obtain preferred toys, the team decides to provide multiples of high-interest toys (e.g., blocks and dump trucks) at school.

Vignette 2: As a prevention strategy, the behavior support team implements the use of a visual schedule with Sophie. On this visual schedule are pictures and text that depict a sequence of events. Adults use this tool with Sophie to help her see a visual representation of her day (e.g., breakfast, circle time, books, alphabet/numbers, recess, circle time, free play, nap time). The team agrees to provide clear expectations when using the visual schedule with Sophie to help with transitions between activities. They also give 2-minute warnings before the end of a preferred activity.

- Teach the child replacement skills. Replacement skills are skills for the child to use instead of the challenging behavior. Teaching the child appropriate social, behavioral, and communication skills allows him/her to successfully participate in everyday activities and routines. Caregivers should provide the child with consistent positive reinforcement when used.

- Provide consequence strategies. Consequence strategies provide guidelines for how the child’s caregivers should respond to the child’s challenging behavior. This is to ensure that the behavior is not maintained and the new replacement skill is learned. The team can discuss their actions and responses to the child across settings, and then brainstorm appropriate ways to respond.

Step 5. Identify training needs. Support your providers/teachers as they identify their professional development goals and training needs. They should feel prepared and comfortable conducting an FBA and developing and using a behavior support plan. Take into account if providers/teachers are unfamiliar with the process or if they have some experience. For providers/teachers who have not done this before, an in-person training led by a behavior specialist may be helpful.

If meeting in person is not feasible, additional support is available online. The Center for the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning (CSEFEL) offers free, comprehensive online modules that address topics such as determining the meaning of challenging behavior (see Module 3a) and developing a behavior support plan (see Module 3b).

Have a conversation with providers/teachers about their strengths and challenges related to this process.

Vignette 1: Shaun’s teacher, Ms. Johnson, sees the value in collecting information on what predicts and maintains Shaun’s challenging behavior. However, she explains that she needs help recording this information. Her director, Ms. Holloway, helps Ms. Johnson develop the following goal: I will work with my team to gather and document in a systematic way information about what predicts and sustains Shaun’s challenging behavior.

Ms. Holloway and Ms. Johnson then discuss possible strategies to accomplish this goal. Ms. Holloway proposes that she can give Ms. Johnson forms to record the appropriate information about Shaun’s behavior. Ms. Johnson thinks this will help but also admits that she’s most likely to use these forms if there’s designated time for someone to go over the forms with her to ensure she’s using them properly.

Vignette 2: Mr. Brown describes how he and his team have completed different observation and interview forms documenting Sophie’s challenging behavior. However, he’s not sure how to make sense of all the information they’ve collected. His director, Ms. Anderson, and he jointly decide on the following goal: I will work with my team to analyze the information collected about Sophie’s challenging behavior to develop a behavior hypothesis statement.

They then brainstorm ways Mr. Brown can accomplish this goal. Ms. Anderson thinks that the school psychologist, Ms. Espinosa, can help Mr. Brown with analyzing the FBA data. Mr. Brown thinks the larger team he works with would also benefit from meeting with Ms. Espinosa.

Step 6. Plan course of action. After identifying professional development goals and needs, you should work with providers/teachers to identify action steps to help them accomplish their goals.

Vignette 1: The director, Ms. Holloway, reaches out to the program’s behavior specialist, Ms. Flowers, to arrange a time to hold a training session about how to use FBA tools (e.g., ABC (Antecedents, Behavior, Consequences) Form, Context Card Form, and Functional Assessment Interview Form) for Shaun’s teacher Ms. Johnson and the behavior support team members. Ms. Flowers leads a 1-hour training session with the entire team. They watch video clip vignettes and practice completing the FBA forms. Ms. Flowers also observes Shaun in the classroom during free play time and recess across two days, and works with Ms. Johnson to complete the ABC form. Ms. Flowers encourages Ms. Johnson to reach out to her with any further questions.

Ms. Flowers then instructs the team to use these FBA tools to collect data about Shaun’s behavior. This information will be used to design an individualized behavior support plan for Shaun. Using the ABC Form and Context Card Form, the team is instructed to record each instance of Shaun’s challenging behavior for the next 2 weeks. They then schedule a follow-up meeting to evaluate the data they’ve collected and come up with a behavior hypothesis statement: “When another child tries to take a toy that Shaun is playing with or near, Shaun hits, kicks, or pinches the child. As a result, the other child drops the toy and finds a new one. Shaun uses this behavior to obtain desired toys.”

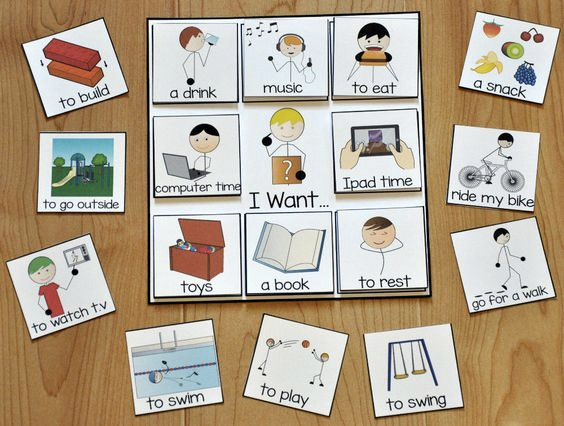

Ms. Holloway schedules a training to review strategies for responding to Shaun’s challenging behavior. They decide to hold weekly team meetings as they begin to implement Shaun’s behavior support plan. If they see that Shaun is about to use physical aggression to obtain a toy, they agree to prompt Shaun to say, “My turn” and “Can I play?” and redirect him to use his choice board to point to the toys he wants to play with. They also continue documenting Shaun’s behavior using the ABC forms. Each week, they come together to track Shaun’s progress by reviewing their observation data, discussing challenges, and identifying what’s been working well.

Vignette 2: The school director, Ms. Anderson, asks Ms. Espinosa, the school psychologist, to join Sophie’s next behavior support team meeting to help the team analyze the data they collected last week. Ms. Espinosa and the team review the information collected on the scatter plot, which shows the frequency of Sophie’s challenging behaviors during which classroom routines. Ms. Espinosa facilitates a discussion about the data, and the team notices that Sophie’s challenging behaviors are most likely to occur during transitions to circle activities. They discuss how Sophie loses interest during songs and stories she doesn’t like. The group also reviews the Antecedents, Behavior, Consequences (ABC) form they completed to further examine what happens during circle time activities for Sophie. Collaboratively, the team uses the data to develop the following behavior hypothesis statement: “When the provider announces it’s time to transition to circle time, Sophie cries and refuses to participate, either by lying on the ground or running away. As a result, the provider asks the aide to quietly work with Sophie at a table. Sophie uses this behavior to escape non-preferred activities and obtain attention from an adult.”

Ms. Espinosa reminds the team that it is crucial to consistently use Sophie’s visual schedule with her throughout the day at school and at home. With time, this will become more manageable, as Sophie learns to use the visual schedule to ask for a break rather than crying or lying on the floor during circle time. Ms. Espinosa provides support to all team members, including Sophie’s parents, by helping them create the visual schedule together and writing reminder notes to ensure that they give Sophie 2-minute warnings before the end of each preferred activity. She also refers the team to the CSEFEL inventory of tools if they need more practice.

Step 7. Acknowledge progress. It is important to recognize the progress that providers/teachers and team members of the child’s behavior support team make. It is also encouraging for team members to acknowledge each other’s achievements.

- Team members can acknowledge each other’s achievements through “shout outs” in regular emails, meetings, or newsletters.

Vignette 1: “Congratulations to Ms. Johnson and her team for implementing an assessment-based behavior support plan for one of her children! The team’s time and dedication to this process are greatly appreciated!”

- Program leaders can personally call or send handwritten notes to thank family members who are participating in the process.

Vignette 1: Ms. Holloway writes a note to Shaun’s grandmother to thank her for coming in after school to answer interview questions about her grandson’s behavior at home. She also thanks her for her commitment to working with the teachers to support her grandson’s success at school and to implement his behavior support plan at home.

- Program leaders can develop a system so parents or other caregivers at home can send handwritten thank you notes to providers/teachers and staff on the behavior support team.

Vignette 2: Sophie’s mom sends a note to Sophie’s provider Mr. Brown that says, “Thank you for giving Sophie better strategies to use whenever she encounters an activity that she doesn’t like at school. We are using the same strategies with her at home, and it has been making things a lot easier!”

- Team members can acknowledge one another during team meetings (e.g., gift card for a local coffee shop) with a few words thanking them for a specific task.

Vignette 2: “Thanks, Mr. Brown and Ms. Peterson, for carefully recording information about Sophie’s behavior on the scatter plot form. It really helped us figure out during which classroom routines Sophie’s challenging behavior is most likely to happen.”

Step 8. Assess progress and new needs. It is important to remember that establishing and implementing an individualized intervention for children with persistent challenging behavior is an iterative process. It is one that should continually be assessed to understand what is and is not working well so that adjustments and refinements to the behavior support plan can be made.

One circumstance that illustrates the importance of monitoring progress and assessing for new needs is the chance that the behavior support team misinterprets the function of the challenging behavior. This could impose a consequence that actually reinforces the behavior instead of reducing it. For example, a behavior support team may initially hypothesize that the child is seeking attention. However, when the child’s behavior does not improve after the behavior support plan is implemented, the team may collect additional FBA information and reanalyze the data. They may find that the child is actually using the challenging behavior to avoid attention. This additional information can help the team revise the behavior hypothesis statement and adjust the behavior support plan to more effectively reduce the challenging behavior.

In order to make necessary adjustments to the behavior support plan and to offer continual support where needed, administrators should meet regularly with team members. Regular team meetings and check-ins allow team members to identify, share, and troubleshoot challenges.

Once a child’s behavior support plan is implemented, it could be valuable to hold a reflection session for the team to compile a list of “pluses” (what worked well) and “deltas” (what the team would like to change in the future). Equally important is to brainstorm strategies for addressing deltas. Team members can learn from each other by meeting or creating a document to share lessons learned and strategies found to be effective.

Vignette 1: Ms. Johnson informs the team that things are going well at school for Shaun. After getting additional support from Ms. Flowers on consequence strategies, she has modified her responses to his challenging behavior and has even helped her teaching assistants provide appropriate reinforcement to other children.

Shaun’s parents note that he is very responsive to using the choice board and is now requesting to play with other toys besides the dump truck and blocks. As a next step, the team decides to incorporate scripted stories about sharing and turn taking with the whole class during circle time.

Vignette 1: Mr. Brown expressed that he’s been struggling with recording the frequency of Shaun’s challenging behavior on the scatter plot form especially when he is busy instructing the class. He’s asked his aide, Ms. Peterson, to help with observing and documenting the information for Sophie’s scatter plot. He commented that Ms. Peterson was eager to help and has been a key player on their behavior support team.

Sophie’s behavior support team looks at data tracking the frequency of her challenging behaviors. They had seen improvements when they first implemented the behavior support plan but are noticing that her challenging behaviors are starting to reappear in certain situations. After the team meeting, Mr. Brown notices that the new aide who started this week, Ms. Hunter, quietly works with Sophie one-on-one when she lies on the floor instead of first redirecting her to her visual schedule to request a break. Mr. Brown asks Ms. Espinosa, the behavior specialist, to work with Ms. Hunter to ensure she receives appropriate training and is brought up to speed on Sophie’s plan. They also invite Ms. Hunter to participate in their team meetings.

What Barriers Might I Run Into and What Are Solutions?

Potential Barrier: Providers/teachers lack the time and expertise to conduct a functional behavior assessment and develop a behavior support plan.

Solution: It is important to remember that the process for establishing and implementing an assessment-based behavior support plan is most effective as a team-based process. Having a behavior specialist/consultant on the team may be a good idea to serve as a source of expertise and training for your providers/teachers so that they feel supported at every step. Parents and families are essential to this process and involving caregivers with whom the child interacts on a daily basis promotes the child’s success in learning replacement skills across all settings.

Potential Barrier: Engaging the family.

Solution: Time constraints and teaming can be a challenge for the whole team. However, because this is a team-based process, every effort should be made to involve all team members, especially the parents of the child. Effective collaboration depends on good leadership and building relationships, and successful teaming is achieved when team members are actively participating in the process and feel like their input is being valued.

- Attend periodic parent-teacher conferences to meet parents and make the effort to learn more about the child or what’s going on at home. Communication is key.

- Create a safe environment at team meetings to foster open communication among team members.

- Build rapport and help to facilitate the conversation so that everyone has a chance to have his/her voice heard. (Parents and family members can give insight to how, when, and why a child’s challenging behavior occurs because they may observe it at home, on the playground, at a family member’s house, at the grocery store, with siblings, etc.)

- Ensure that all team members are actively participating in goal setting and plan development. This helps to keep team members invested in the process, so that everyone is on the same page and has a “shared vision”7 for the child. Goals should be agreed upon and attainable.

- Integrate the FBA and behavior support plan process into already existing IEP/IFSP meetings. One or both parents are required to attend IEP/IFSP meetings, so this will help ensure their participation in the process.

- Emphasize to parents and family members that additional support and training resources are always available (see Where do I go for more resources?)

- See the following resources for more information on teaming:

Potential Barrier: Student absences are making it difficult to implement the behavior support plan.

Solution: Program leaders and providers/teachers should reach out to parents and/or other caregivers and explain that the behavior support plan is most effective when the child is taught replacement skills across settings. Responses to the child’s behavior should also be consistent across settings. This means that the child should receive positive reinforcement for appropriate behavior not only at school but also at home. Repetition and consistency are key to reducing a child’s challenging behavior, and thus can reduce the likelihood of suspension/expulsion.

Where do I go for more resources?

- New Resource: For strategies that providers/teachers can use with individual children, see this brief tip sheet by the Pyramid Equity Project that includes eleven of the most effective strategies for responding to challenging behaviors.

- To learn more about the reasons for challenging behavior and effective strategies for responding, watch this video by the Connecticut Office of Early Education.

- For step-by-step guidance, tools, and examples specifically related to conducting a functional behavioral assessment and developing a behavior support plan, visit the National Center for Pyramid Model Innovations (NCPMI) and review the Complete Guide to Positive Behavior Support.

- For training resources on FBA and behavior support plans visit the Center on the Social and Emotional Foundation in Early Learning (CSEFEL), which includes PowerPoint presentations, handouts, presenter scripts, and video clips (also available in Spanish):

- For more information about practical strategies for helping young children with challenging behavior, visit the Center for Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation website on Creating Teaching Tools for Young Children with Challenging Behavior.

- For scenarios and strategies to use in training and professional development with your staff related to behavior management, see the Early Childhood Behavior Management Case Study Unit by the IRIS Center Case Study Unit.

- For additional examples and vignettes that illustrate how practical strategies might be used in a variety of early childhood settings and home environments, visit the What Works Briefs series on the CSEFEL website. These Briefs include short, easy-to-read “how to” information packets on a variety of evidence-based practices, strategies, and intervention procedures designed to help providers/teachers support young children’s social and emotional development.

References

Artman-Meeker, K., & Hemmeter, M. L. (2014). Functional assessment of challenging behaviors. In M. McLean, M. L. Hemmeter, & P. Snyder (Eds.), Essential elements for assessing infants and preschoolers with special needs (pp. 242-270). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Conroy, M. A., Davis, C. A., Fox, J. J., & Brown, W. H. (2002). Functional assessment of behavior and effective supports for young children with challenging behaviors. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 27(4), 35-47.

Division of Early Childhood of the Council for Exceptional Children. (2015). Recommended practices glossary. Retrieved from http://www.dec-sped.org/dec-recommended-practices

Fox, L., Carta, J., Strain, P., Dunlap, G., & Hemmeter, M. L. (2010). Response to intervention and the pyramid model. Infants and Young Children, 23, 3 – 13.

Fox, L., & Duda, M. A. (n.d.). Positive behavior support. Technical Assistance Center on Social Emotional Intervention for Young Children. Retrieved from challengingbehavior.fmhi.usf.edu/explore/pbs_docs/pbs_complete.doc

Individualized Intensive Interventions: Developing a Behavior Support Plan [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://csefel.vanderbilt.edu/resources/training_preschool.html#mod3b

McLaren, E. M., & Nelson, C. M. (2008). Using functional behavior assessment to develop behavior interventions for students in Head Start. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions.

Sugai, G., Horner, R. H., Dunlap, G., Hieneman, M., Lewis, T. J., Nelson, C. M., Scott, T., Liaupsin, C., Sailor, W., Turnbull, A. P., Turnbull, H. R., Wickham, D., Wilcox, B., & Ruef, M. (2000). Applying positive behavior support and functional behavioral assessment in schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 2(3), 131-143.

Technical Assistance Center on Social Emotional Intervention for Young Children (2011). The Process of Positive Behavior Support (PBS), Step Five: Behavior Support Plan Development. Retrieved from http://challengingbehavior.fmhi.usf.edu/explore/pbs/step5.htm