– How do I do this?

– What Barriers Might I Run Into and What Are Solutions?

– Where do I go for more resources?

– References

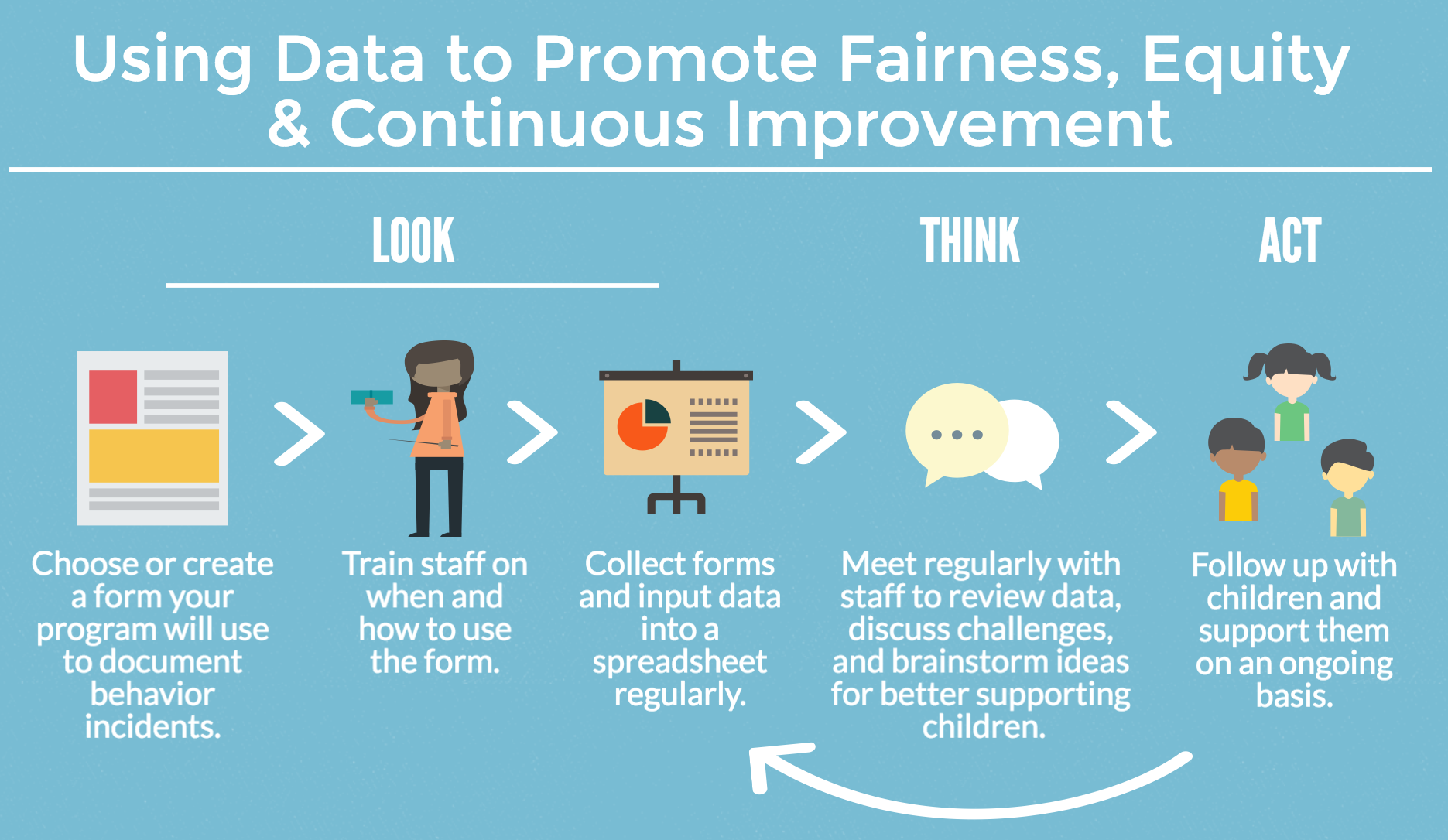

“Fairness, equity, and continuous improvement” in early childhood programs are crucial for improving school climate and school discipline, say the U.S. Departments of Education and Health and Human Services. All programs need to set their own goals, monitor data to assess progress, and modify practices as needed to reach their fairness, equity, and improvement goals.

Collecting data to monitor your progress about disciplinary policies and practices can help in a number of ways:

- Data can help you understand how exclusionary discipline is used at your school and help you see areas of policy and practice in need of change. In order to track a reduction in the use of suspension and expulsion, you must first clearly define what they are (e.g., suspension can be asking parents to pick up early, as well as asking the child to stay home for a number of days). Then you must keep records of how frequently and under what circumstances these practices are used. If programs do not pay regular attention to their discipline data, it will be hard to build on what works well or change a policy that does not work as well as hoped.

- Data will let you track progress as you try new policies. Data can help you see whether you really are using less exclusionary discipline and applying discipline fairly across groups of children.

- Finally, more transparency about how your program handles discipline can help the program/school community build trust, among staff, and with families and children. To do this, programs need to separate out discipline data by subgroups, including by race, gender, and children with Individualized Family Service Plans (IFSPs) or Individualized Education Plans (IEPs). These data should be publicly available. The data should include information about the characteristics of children in your program and disciplinary activities. This should include

- the percentage of children who are White, Black, male, female;

- the percentage of children who have an identified disability or IFSP/IEP; and

- how many children of each group are suspended or expelled within a certain time frame.

Review of these data lets you and your program staff clearly see how often children are disciplined for various behaviors. These data also show whether there is disproportionality, meaning that certain groups of children are disciplined more or less often than other groups of children for the same types of behaviors.

How do I do this?

Use a standard format to document discipline (such as a behavior incident report form). Write down factors related to disproportionality for the children involved, such as their race, gender, and whether they have an IFSP/IEP. Also include time, place, antecedents, teacher or staff involved, and any disciplinary action taken, including suspension and expulsion. You may want to have teachers record efforts to use positive management strategies as well, so that they can focus on improving prevention support to reduce the need for exclusionary discipline.

- Looking for a behavior incident report form template? See the National Center for Pyramid Model Innovations (NCPMI) Incident Report System.

Create a systematic process for recording discipline. This will encourage staff to be accountable for how they respond to children’s behaviors. This will also help staff be transparent. Stress that the information gathered will be used to make your program better and not to evaluate staff, and then stick to your word.

Create processes for entering and analyzing the data. Choose a staff member who will serve as “data champion.” This person will be responsible for entering and analyzing the data. Support this person in gaining the skills and the time necessary to do this work, such as learning to use Microsoft Excel for entering and managing the data. Set a timeline for how often data should be entered and analyzed, such as once a week, or twice a month.

- This template from NCPMI can help track monthly program actions related to behavior incidents and concerns.

- New Resource: This fact sheet from The Pyramid Equity Project explains different ways to look at disproportionality in discipline and behavior incidents.

Examine the data with staff in an open and constructive way. Aim to identify patterns in behavior incidents by child and by subgroups of children. For example, choose one child who struggles with behavior, and try to find out if the child is usually involved in incidents at the same time of day or with the same peer. Also examine whether there is disproportionality in discipline in your program/school. For instance, are certain groups (e.g., Black boys) being disciplined more often or more harshly than other groups for the same types of behaviors, or are some providers/teachers disciplining children more than others are?

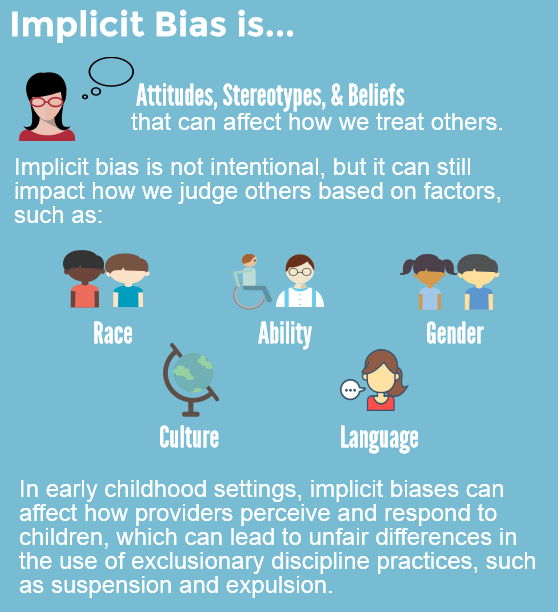

Acknowledge challenges, set goals for improvement, and identify steps for achieving these goals. For example, if the data show that exclusionary discipline is often used as a response to children’s challenging behaviors, set goals to reduce suspensions and expulsions by a specific amount within a certain time frame. If the data show there is disproportionality, set goals to reduce this as well. Work with staff to write a plan with explicit steps for reaching these goals, including using strategies described under the other recommendations on this site, such as building cultural understanding between families and staff in order to minimize misconceptions and implicit biases that contribute to disproportionality in use of exclusionary discipline.

-

-

- Continue to collect and analyze data as a way to see whether you are making progress toward these goals.

- For a template form to track monthly program actions related to behavioral incidents and concerns, see this template from NCPMI.

-

Build in a process for follow-up support for children involved in behavior incidents. In addition to standardizing how you document incidents, standardize steps taken to support the child following an incident. This might include holding a parent meeting, referring to specialists when necessary, and having a behavior support plan in place (see Recommendations 3.1 and 3.2).

What Barriers Might I Run Into and What Are Solutions?

Potential Barrier: My staff may not have the time, resources, and skills needed to collect and analyze data.

Solution: We recognize that these are difficult challenges to overcome. Simple things such as asking teachers to take turns in entering discipline data, or asking an administrative assistant to act as “data champion” may help. Addressing them may also require getting creative and seeking resources in the community, such as local university students, who may be able to provide support and guidance on collecting and analyzing data. If you are able to put a data system in place, your efforts may be rewarded through beneficial “side effects,” such as increased adult accountability (due to having clear guidelines around what counts as a behavior incident that must be documented, including documenting the role the adult played) and some level of legal protection due to the existence of formal records that capture staff efforts. To easily enter, summarize, and look at graphs of data related to behavior incidents and program actions, use this Behavior Incident Report System created by NCPMI that is set up to do just that automatically.

Potential Barrier: Many providers/teachers and administrators base their decisions on their experience, intuition, and professional judgment, not on information that is collected systematically.

Solution: Inspire a change in perspective by educating staff about the benefits of data-driven (rather than intuition-driven) decision-making. These include avoiding biased judgments, being more consistent across staff and situations, and being able to measure change over time. Make the use of data as nonthreatening as possible by being transparent at every step. Talk with staff about how data can be used to complement and support their professional judgment, not replace it.

Potential Barrier: Some providers/teachers may not see or fully appreciate how their own behaviors and actions impact the behaviors and actions of the children they work with, which leads them to overlook useful data.

Solution: Again, inspire a change in perspective by educating staff about how their own behaviors and actions are related to those of the children they teach because of the back-and-forth nature of social interactions. How staff interact with children and address challenging behavior is an important aspect of the behavior incident that must also be examined, learned from, and improved on.

Potential Barrier: Data on disproportionality in suspensions and expulsions may be considered sensitive. Staff may have fears that information will be used politically or punitively, making staff mistrust or avoid data.

Solution: This is an understandable fear. Care must be taken to build trust among staff and administrators and to use findings from analyses only to improve the practice and support staff. Policies about data collection and use should be set through a collaborative process and then applied equally to all staff, regardless of role. For example, all staff will use a standardized behavior incident report to record incidents they are involved in. All staff will receive feedback on their approaches to addressing challenging behaviors and how often they used exclusionary discipline to respond to a child’s challenging behaviors in a certain time frame.

Where do I go for more resources?

-

-

- New Resource: See this fact sheet from the Pyramid Equity Project on different ways that programs can look at disproportionality in discipline and behavior incidents.

- For a complete behavior incident report system to collect and analyze behavior incidents in a program, see this package of tools from NCPMI—the tools are useful even if you aren’t using the Pyramid Model.

- To track monthly program actions related to behavior incidents and concerns, see this template from NCPMI.

- To learn more about Evidence Based Decision-Making, view this summary and guidance document.

- Want tips on how to share data effectively with your staff and families? Check out the DaSy Data Visualization Toolkit.

- For videos of family, practitioner, and administrator data use, see the Perspectives on Data Use videos from the DaSy Center.

- Watch this 4 min. video of real teachers discussing how using data is just part of good teaching and how they benefit from using data.

- This report from the Regional Educational Laboratory Northeast & Islands (REL NE) identifies considerations for conducting analysis of child/student-level disciplinary data. These include the data elements to be used in the analysis and establishing rules for transparency. The report also covers examples of descriptive analyses that can be conducted by programs/districts to answer questions about the use of the disciplinary actions.

-

References

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Education. (2014). Policy Statement on Expulsion and Suspension Policies in Early Childhood Settings. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/policy/gen/guid/school-discipline/policy-statement-ece-expulsions-suspensions.pdf

Skiba, R. J. and Losen, D. J. (Winter 2015-2016). From recreation to prevention: Turning the page on school discipline. American Educator (pp. 4-11). Retrieved from http://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/ae_winter2015skiba_losen.pdf