– How do I do this?

– What Barriers Might I Run Into and What Are Solutions?

– Where do I go for more resources?

– References

Back to Recommendations

Infant/Young children’s mental health is a public health concern. Challenging behavior is common in children birth to age 5 but can reach clinically significant levels at times. Infant/Young children with challenging behaviors are more at risk for being suspended or expelled, even later in life. About 20% of school-aged children show challenging behaviors that are linked to mental health problems, and 10% to 15% display psychiatric disorders (e.g., anxiety; aggression) that affect their behavior even more. However, many children do not have access to the services they need, and many services offered are not high in quality.

An infant/early childhood mental health consultant (I/ECMHC) is someone who can support infant/child development by building the skills and capacities of caregivers, program leaders, and parents/families. For example, I/ECMHC can help staff build skills around behavior and classroom management and increase developmentally appropriate practices and expectations. In fact, there is accumulating evidence that developing practitioner skills that promote the positive social-emotional development of all infants/children, can help to reduce suspensions and expulsions.

Note: When we refer to “children” throughout the rest of this text, we are referring to children birth to age five.

Infant/Early Childhood Mental Health Consultant (I/ECMHC)

- The I/ECMHC approach creates teams composed of a mental health professional with an individual or groups of early childhood care providers in an ongoing problem-solving and capacity-building relationship. I/ECMHCs seek to improve child outcomes through changes made in the classroom environment (e.g., routines) and by helping teachers, staff, and other caregivers gain new skills. Emphasis is on building teachers’ skills and capacities through careful observation of individual children, screening, and modeling effective practices.

- It will be helpful to have a conversation with an I/ECMHC to clarify program needs and priorities. I/ECMHCs can provide a range of services that are carefully tailored to meet the needs of the children and families that programs serve. However, it is imperative to understand that I/ECMHC serve as consultants – not as therapists whose purpose is to “fix” children.

- Consultants can support your program and promote children’s social-emotional development through:

- Early identification of children with social-emotional and behavioral concerns, such as screenings and making referrals for children and families with more serious concerns.

- Building staff capacity to promote the social-emotional development of all children in the program and addressing challenging behaviors, through:

- problem-solving alongside the teacher,

- modeling effective methods of interacting with children, and

- improving the program’s climate, structure, and day-to-day operation.

- Guiding or facilitating self-reflection, where workplace stressors or complex professional topics (such as implicit bias) can be discussed and addressed in a safe space.

- Working with administrators, staff, and family members of children in your program to reduce problem behaviors and build positive social-emotional skills by:

- developing and implementing classroom-based interventions alongside teachers,

- supervising family-outreach workers,

- providing crisis interventions in the face of community or family disasters, and

- running parent groups.

This 2-minute video from the Mental Health Consultation Tool learning module provides a broad overview of how a mental health consultant works systemically with program leaders, staff, families and children.

Want to see a more in-depth example of how an I/ECMHC helped a program and family manage a young chid’s biting behaviors?

How do I do this?

Does your program already have access to an early childhood mental health consultant?

If your program already has access to an I/ECMHC, you can use the following needs assessment survey from the Georgetown University Center for Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation:

- The purpose of this tool is to collect information about the strengths and weaknesses of your current ECMH program services based on current best practices. Upon completion of the survey, this online tool can link you to information and resources that can help to strengthen your ECMH services.

If your program does not have access to an I/ECMHC, proceed to Step 1.

Step 1. Assess the I/ECMHC options. Determine which consultation and delivery format best fits your program’s priorities. Discuss and consider the perspectives of providers/teachers as well as families with a planning team (see Step 2 for more details on the planning team). As you review the possibilities outlined below, it is helpful to take stock of what program and community resources and services are accessible or already in place. This includes determining whether your state has a statewide approach to I/ECMHC.

There are three basic early childhood mental health consultation formats:

- Classroom-specific consultation, which focuses on improving the quality of teacher-child interactions and classroom behavior management.

- Child-specific consultation, which focuses on strengthening teachers’ strategies for developing children’s behavioral and social-emotional skills, parent/caregiver partnerships, and referrals for specific children.

- Program-wide approach, which not only provides I/ECMHC services to all of the providers and children in a program, but also works with the director to examine and improve program policies and procedures to better support social-emotional development and prevent expulsions/suspensions.

Table 1. Examples of Child- and Classroom-Specific Consultation Services

| For Children: Conduct individual child observations Design and implement program practices responsive to the identified needs of the child Provide one-on-one modeling or coaching to support an individual child Provide crisis intervention services for staff regarding a child’s behavior Advise and connect staff to community resources and services Provide support for reflective practices |

For Families: Offer training on behavior management techniques Provide one-on-one modeling to support an individual child Educate parents on mental health issues and refer them to health services located in community Conduct home visits Advocate for parents |

| For Staff: Conduct classroom observations and evaluate the center or learning environment Train staff on behavior management techniques and accessing mental health resources Suggest strategies for classroom management Support staff working with children with challenging behaviors |

For Programs: Promote staff wellness by addressing issues related to communication and promote team building Train staff to use culturally responsive and developmentally appropriate practices Design and implement early childhood mental health best practices for your program context Consult with the program director and advise on issues related to program needs and policies |

Note. This table has been abridged and summarized for the purposes of this guide.

Case Study: Connecticut’s Early Childhood Consultation Partnership (ECCP)

To date, the success of this state-wide program has been proven through three rigorous random control trials. The ECCP is an evidence-based, mental health consultation program to address the high rates of suspension and expulsion of preschool children in child care settings. It is one of the few programs in the country serving infants, toddlers, and preschoolers. The Department of Children and Families in Connecticut uses this program, and its efforts have been documented in a U.S. News & World Report article.

- For more details about Connecticut’s Early Childhood Consultation Partnership, please see the ECCP website. We recommend that those interested visit the (“Program Facts” page). This section of the website has more details about the kinds of services I/ECMHCs offer and how the program is implemented in programs across the state. The documentation of partners and contractors, funding sources, and issues related to the workforce might also be helpful.

Step 2. Plan a course of action to put in place the core features needed for an I/ECMHC to succeed. The key to effective early childhood mental health consultation lies in the consultant’s ability to develop a positive, collaborative partnership with teachers and staff. This relationship is built and sustained through effective communication. To help prevent suspensions and expulsions, an effective I/ECMHC consultation program follows these core steps:

- Develop a program-wide vision of what mental health looks like for children in your program.

- Create a strategic plan co-constructed by a planning team with agreed-on goals.

- Develop and prioritize which goals your strategic planning team would like to achieve. Be careful to also specify the roles and responsibilities of families, providers/teachers, and staff.

- Identify a trained and qualified ECMHC who uses evidence-based practices

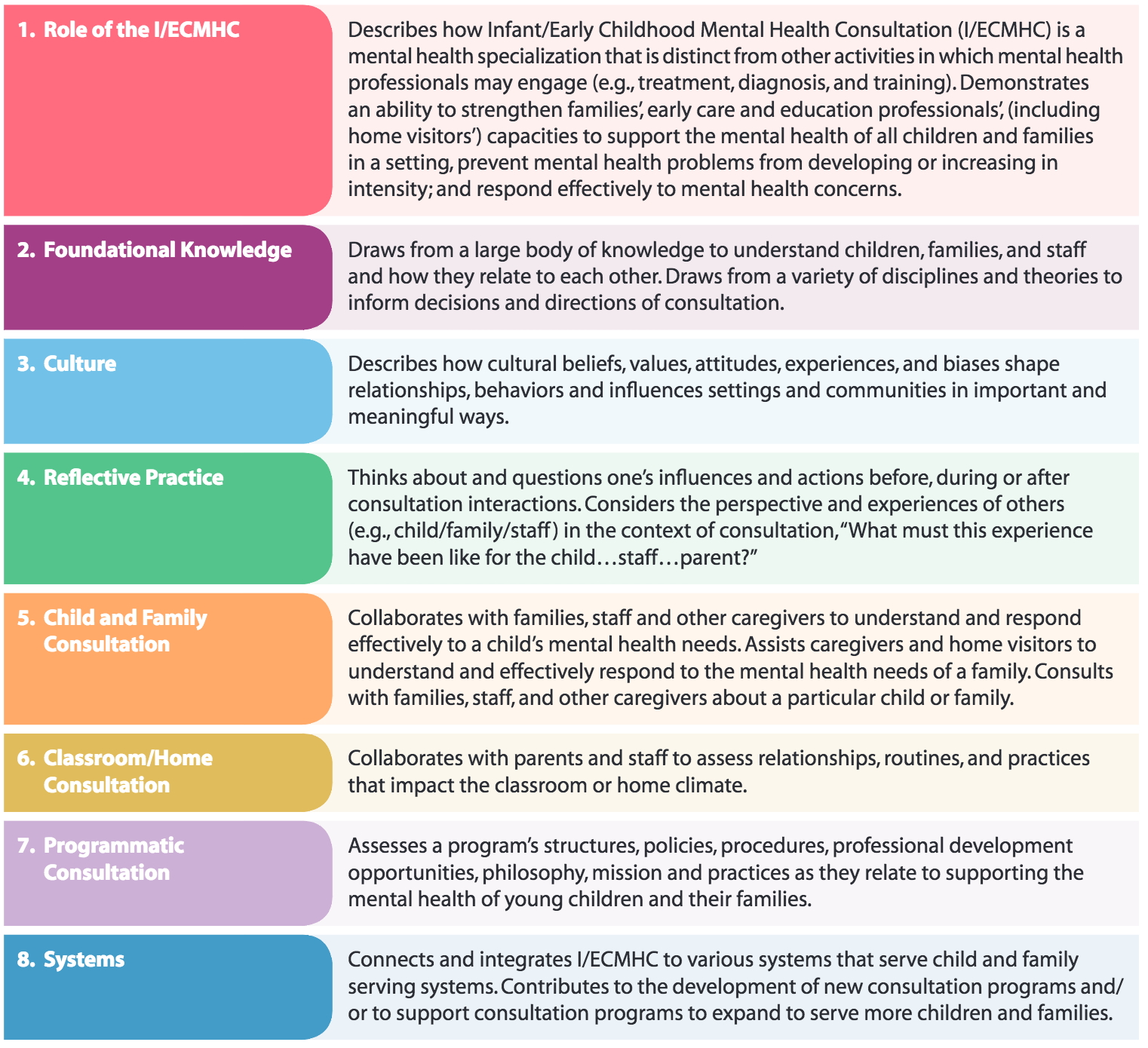

Table 3. I/ECMHC Core Competencies

Source: Infant/Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation National Competencies from the Office of Head Start’s Infant/Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation (I/ECMHC) learning module.

- Collaborate with other early childhood service providers such as IDEA service providers, home visitors, or family outreach specialists.

- Communicate with staff and families and promote buy-in.

- Assess progress and new needs.

What Barriers Might I Run Into and What Are Solutions?

Potential Barrier: Staff and families are resistant because of the stigma attached to mental health services.

Solution: Some families might be hesitant to use mental health services because of stigma. Schools are a logical and convenient environment to deliver mental health services. Program-based services help lower barriers that stop children from having access to mental health services. These barriers can include travel time and transportation access, parents/caregivers’ having to take time off work, and lack of knowledge about where to seek help. Services provided in programs also help get around the real and perceived stigma of seeking services through traditional mental health service providers—services are instead provided in a familiar and trusted setting. Importantly, services are also administered in partnership with another trusted caregiver (teacher, teaching aide, paraeducators). The classroom is a useful environment for children to practice skills in real-life settings with teachers and peers, increasing the chances that these skills will solidify.

- To help educate staff and families on what early childhood mental health is and looks like, check out this 5-minute video put together by the Center for the Developing Child at Harvard University, which explains early childhood mental health.

Potential Barrier: How will we know when to seek the services of an EI/ECMHC?

Solution: Challenging behavior does not need to meet clinical definitions in order to hire an EMHC practitioner. In fact, working with an I/ECMHC may help keep challenging behaviors from escalating and carrying over into other contexts (e.g., by identifying the causes of intense tantrum behaviors that are not easily soothed in school, the I/ECMHC can help parents and caregivers develop strategies to prevent such behavior out of school).

- For real life scenarios and guidelines, check out this two-page brief from the Center on the Social Emotional Foundations for Early Learning (CSEFEL) on when to seek outside help for children’s behavior.

Potential Barrier: My program lacks funding to support an I/ECMHC.

Solution: Investing in an I/ECMHC is argued to be cost-effective and justified as a method of preventing the extremely high costs associated with treating behavioral problems in later school years (e.g., grade retention, contact with the juvenile justice system) and at later points in life (e.g., mental health services).

- This document describes federal funding streams that can be paired with state and local funds to support the hiring of an I/ECMHC.

- Consider partnering with a Head Start program, all of which are required to have an I/ECMHC or with other mental health agencies that may have grants or funds to provide services for free or at a discounted rate to people in their community. For example, the state of Louisiana offers free I/ECMHC to all programs in the QRIS while Connecticut offers it to any providers who work with children under the age of 5.

Potential Barrier: My program lacks resources or funding in general.

Solution: Your local Child Care Resource and Referral agency can help you find local free and low-cost training opportunities. They can also help you find grants for additional funding and resources.

- You can locate Child Care Resource and Referral agencies in your area through Child Care Aware’s search tool. Its State by State Resource Map can point you in the right direction for local resources on child care, health and social services, financial assistance, support for children with special needs, and more.

Where do I go for more resources?

- Developing and Implementing a Program-Wide Vision for Effective Mental Health Consultation. This is a tool kit to support Early/Head Start administrators in promoting program-wide mental health through an I/ECMHC. This tool kit addresses topics such as (1) developing a mental health vision, (2) building a mental health strategic plan, (3) the foundations for implementing your strategic plan, (4) hiring an I/ECMHC, (5) building and using a mental health work group, and (6) accountability and continuous quality improvement.

- Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation: An Evaluation Tool Kit. This tool kit provides a more comprehensive description of the defining characteristics and core features of an I/ECMHC. The document also contains information about how to develop a plan to evaluate how the I/ECMHC impacts the outcomes of children and their families

- The Center for Excellence for Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation. This is a resource page from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration, an agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The I/ECMHC Toolbox offers information about the latest research and best practices for I/ECMHC in infant and early childhood settings. It provides free interactive planning tools, guides, videos, and additional resources to support I/ECMHC efforts in states, tribes, or communities.

- Center for Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation. This is a website developed by Georgetown University’s Center for Child and Human Development that provides links to materials that addresses the questions and needs of I/ECMHCs, Head Start program administrators, Head Start staff, training and technical assistance providers, and families.

- Mental Health Consultation Tool. This webpage is an interactive learning module that includes a needs assessment as well as modules on topics related to workforce development, financing, and cultural issues.

References

Brennan, E. M., Bradley, J. R., Allen, M. D., & Perry, D. F. (2008). The evidence base for mental health consultation in early childhood settings: Research synthesis addressing staff and program outcomes. Early Education and Development, 19(6), 982-1022.

Center for Disease Control. (1999).Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/Library/MentalHealth/chapter2/sec2_1.html

Cohen, E., & Kaufmann, R. K. (2000). Early childhood mental health consultation. Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services.

Cohen & Kaufmann (2005); Donahue, P. J., Falk, B., & Provet, A. G. (2000). Mental health consultation in early childhood. Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Gilliam, W. S. (2007). Early Childhood Consultation Partnership: Results of a random-controlled evaluation. Final Report and Executive Summary. New Haven, CT: Child Study Center, Yale University School of Medicine.

Green, B. L., Everhart, M., Gordon, L., & Gettman, M. G. (2006). Characteristics of effective mental health consultation in early childhood settings multilevel analysis of a national survey. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 26(3), 142-152.

Green, B. L., & Allen, M. D. (2012). Developing and implementing a programwide vision for effective mental health consultation toolkit. Retrieved from http://www.I/ECMHC.org/documents/CI/ECMHC_AdministratorsToolkit.pdf a>

Hepburn, K. S., Kaufmann, R. K., Perry, D. F., Allen, M. D., Brennan, E. M., & Green, B. L. (2007). Early childhood mental health consultation: An evaluation tool kit.

Masia-Warner, C., Klein, R. G., Dent, H. C., Fisher, P. H., Alvir, J., Albano, A. M., & Guardino, M. (2005). School-based intervention for adolescents with social anxiety disorder: Results of a controlled study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(6), 707-722.

Perry, D. F., Allen, M. D., Brennan, E. M., & Bradley, J. R. (2010). The evidence base for mental health consultation in early childhood settings: A research synthesis addressing children’s behavioral outcomes. Early Education and Development, 21(6), 795-824.

Perou, R., Bitsko, R. H., Blumberg, S. J., Pastor, P., Ghandour, R. M., Gfroerer, J. C., … & Parks, S. E. (2013). Mental health surveillance among children—United States, 2005–2011. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 62(2), 1-35.

Stagman, S. M., & Cooper, J. L. (2010). Children’s mental health: What every policymaker should know. Retrieved from https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/catalog/ac:126203

Yoshikawa, H., & Knitzer, J. (1997). Lessons from the Field: Head Start Mental Health Strategies To Meet Changing Needs. National Center for Children in Poverty, Columbia University School of Public Health.